Pulse in Print: The origins of Pulse and its TV-royalty first editor

We look at Pulse’s early years and the TV-royalty editor who first made it happen

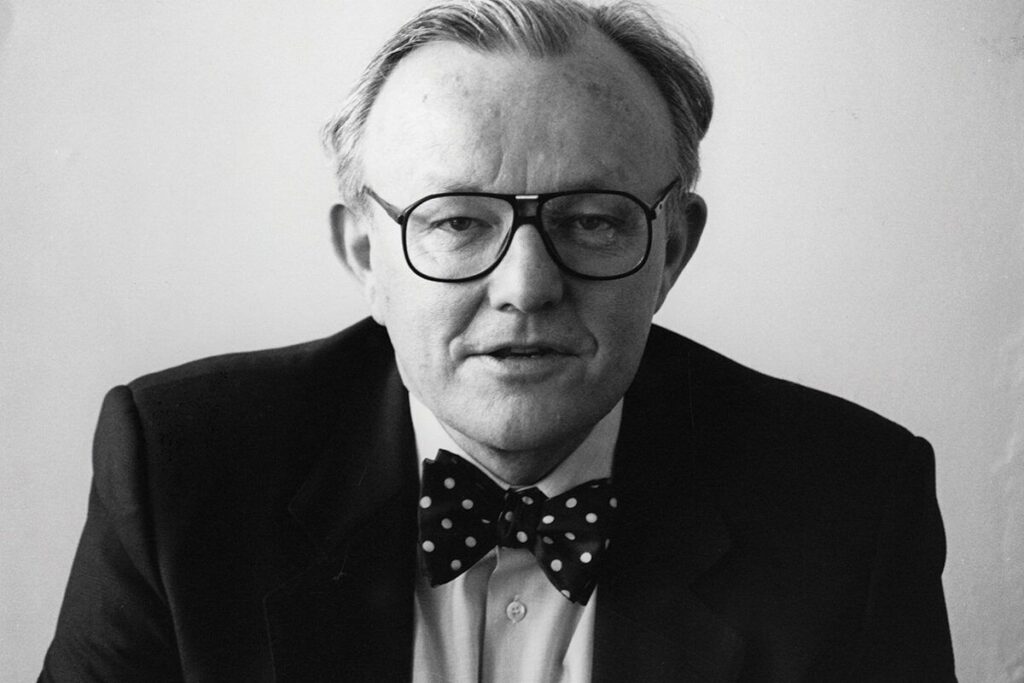

One Wednesday morning in March 2021, Pulse received an email from a Richard Price. Unlike those who usually contact us, Richard did not introduce himself as a GP or a press officer, but as Pulse’s very first editor, who took the helm of the title in 1960.

Describing himself as ‘nearly retired’, Richard – who was 87 when he emailed us – said he had ‘disappeared into the television world’. He described ‘happy memories’ from his two years at Pulse, said it was ‘fascinating’ to see how the title had evolved over the years and congratulated us on our ‘modern layout’ and ‘width of coverage’. He looked forward to becoming a regular reader now that he had more time on his hands.

For our final issue, we got back in touch with Richard. Sadly, his retirement proved shortlived as he passed away in March 2023. But once we started looking into his post-Pulse career, we realised that ‘disappearing into the television world’ was an understatement. He became television royalty, with his company at the heart of some of the biggest TV shows of the time. He even became chair of BAFTA, and recruited contacts to support his charity work.

Here, we take a look at Pulse’s early years and the working life of its first editor.

Launching a newspaper for GPs

Most of you would probably identify Pulse as a colourful print magazine containing everything from news and views to clinical features and investigations.

But in Richard’s day, Dr Copperfield’s ghoulish caricature was nowhere to be seen. That role of sceptical commentary was taken by The Dissector, who entertained readers with columns on the latest developments in general practice in what was then a newspaper with a vested interest in promoting pharmaceuticals.

Pulse was the brainchild of the pharmaceutical company Bayer Products (which, confusingly, was not run by Bayer at the time but was a subsidiary of Stirling Drug). It decided to launch a paper to publicise information about its ever-growing product range to medical professionals. As one pharmaceutical development came on top of another, the company struggled to communicate with the profession. GPs were receiving more and more circulars and more frequent visits by medical representatives, and soon began to complain to Bayer Products. The company did not see it as a problem, but as a challenge to its creative ability, and its solution was a weekly paper that compiled information about the latest pharmaceuticals in one place.

In his email to Pulse, Richard recalled ‘putting the then tiny paper together every Thursday in the old-fashioned format with lead type on the stone’ referring to the 1960s-era letterpress – then a technological marvel but a far cry from the computers and printing presses that produce the magazine today.

The fact that Pulse started as a promotional paper may explain why Richard’s role was envisaged not as a journalist but as a salesman, akin to a PR today, responsible for promoting pharmaceutical products in this innovative new outlet. That soon changed.

Although Bayer Products saw Pulse as an instrument to promote its medicines, Richard and his colleagues believed it had a duty to serve GPs. ‘Pulse must deserve to be read’, they decided.

That’s why, when the first issue appeared in March 1960, it was introduced as ‘a completely new idea in medical journalism’ that aimed to ‘provide 20 minutes or half-an-hour’s relaxation after hours’ as well as ‘information that will help you with your work as a GP’. As such, it offered everything from a special free income tax advisory service to the chance to test-drive and report on the new Ford Anglia. These features sat alongside those promoting the products, such as Panadol for pain relief, Plaquenil for rheumatoid arthritis, and Trancopal for a stiff neck. Bayer Products announced that future issues would include ‘travel articles on unusual places’ and ‘a regular Stock Exchange commentary’, not to mention a special place for ‘the two main doctor-interests, golf and photography’.

Nine months after Pulse launched, popular demand transformed the paper from a fortnightly to a weekly. According to the publisher, it was clear from the growing volume of letters – more than 500 each week – that the paper was both read and valued.

But there were growing concerns among GPs that a directly sponsored paper could be a barrier to ‘reflecting issues of an increasingly critical nature’. In 1961, Bayer Products donated Pulse to the newly formed company Professional Projects Ltd, which would grant it editorial independence.

From that point, Richard had the freedom to publish the stories that mattered most to GPs, which marked the beginning of Pulse’s role as an authoritative voice in the healthcare press.

And more than 60 years on, many of the leading stories from those early days will be remarkably familiar to GPs today, such as the shortage of doctors and the spiralling costs of running a practice.

From medicine to Mamma Mia!

After two years at Pulse, Richard left the land of Panadol and Plaquenil to work for ITV Granada’s international sales team.

A few years later, in 1968, he founded his own production company Richard Price Television Associates (RPTA), which eventually became the Primetime group in 1980. Responsible for more than 7,500 hours of programming, Primetime was the UK’s largest independent television producer.

Its production of Trevor Nunn’s filmed Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) production of The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1982) was nominated for five BAFTAs and won two. Richard worked with Nunn again in the 1990s to bring the RSC’s Oklahoma! (1999) to cinema screens, as well as The Merchant of Venice (2001) and King Lear (2008). He also developed the stage production of Mamma Mia! (1999) and the award-winning historical film The King’s Speech (2010).

Over his career, Richard won numerous accolades for his work. He was made a fellow of the Royal Television Society in 1986 and served as BAFTA chair between 1991 and 1993. He was also awarded an MBE in the New Year Honours of 2000.

When he wasn’t working or attending award ceremonies, Richard was heavily involved in charity work, most notably as chair of trustees and patron of the HFT, which supports adults with learning disabilities across England and Wales, including Richard’s own daughter Annabel who lives in one of the charity’s care homes in Bedfordshire.

Richard’s son Nick says: ‘Because he was such a people person and had such great contacts, my father was able to ask people from the world of media, film and television to help him promote HFT and raise its profile.’ The famous names who have happily supported the charity as patrons include Griff Rhys Jones, Maureen Lipman and Martin Clunes.

Richard’s friend and HFT colleague Richard Barber also commends his tireless work.

‘He was determined to do everything he could to create a better life for people with learning disabilities, and his chairmanship saw a period of tremendous expansion for the charity as new services were started in different parts of the country,’ he says. ‘His boundless energy was never exhausted, from visits to our services with our royal patron Princess Anne and meetings in Parliament to seek government support for social care, to fundraising events such as golf days with Ronnie Corbett.’

And outside the limelight, Mr Barber says Richard was a ‘loving and devoted father’ who was an integral part of the HFT’s team in Bedfordshire, who continue to look after Annabel.

‘He was always kind, generous and witty, and never failed to make the team laugh with his huge sense of humour,’ he says. ‘The manager Sian remembers how every time she spoke to Richard, she would say, “Hello Mr Price, how are you?” And, every time, he would reply, “What a silly question, ask me another one!”’

Margaret Rundall, a fundraiser for the HFT, often approached parents for fundraising ideas and support. ‘If you just mentioned something, Richard would pick up the phone right away,’ she says. For five years, they hosted an annual charity dinner, with guests such as Michael Palin and David Frost. ‘Whenever I went to see Richard, I came out buzzing,’ she recalls.

Despite a stellar career as chair of BAFTA and hobnobbing with the biggest names in television, he never forgot his roots. RPTA colleague Margo Faith said: ‘He was forever talking about Pulse. It was a source of great pride to him.’ Words by Rhiannon Jenkins

Richard was a devoted, passionate and dedicated supporter of HFT (previously named Home Farm Trust) and learning-disabled adults for over 40 years. If you wish to make a donation to HFT, please do so via its website, quoting reference: MAJMRP24.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Related Articles

READERS' COMMENTS [1]

Please note, only GPs are permitted to add comments to articles

A remarkable story. Well done.