Female GP leader numbers growing… but still work to do

In the last part of our investigation on sexism in general practice, Anna Colivicchi looks at imbalances at leadership level

Female GPs still face sexist attitudes and harassment in the practice, hampered career progression and unequal pay. Yet in terms of representation in leadership positions, things do seem to be improving – although, to paraphrase George Orwell, men still remain more equal than women.

We look at the strength of female GP representation in the professional bodies and commissioning bodies – and look into what they means for grassroots GPs.

GPC England and GPC UK

An official report accused in 2019 the BMA’s England GP committee of being an ‘old boys’ network’ – a damning accusation that made the headlines at the time.

The union had come under fire due to reports of sexism within the organisation and commissioned the report, written by Daphne Romney QC, which backed up claims made by female GPC members.

The Omambala report, which followed three years later, found not much had changed for the GPC. And while the union has said it has seen ‘considerable improvement’ since then, it has also admitted that ‘it is nowhere near equality’.

Currently, of four UK GPC national chairs only one is a woman, and of 43 UK-wide elected members, only 13 are women.

As pointed out by a major Pulse investigation in 2022, sexism and a culture that ‘marginalised women and ethnic minorities’ within the union meant that large parts of the GP workforce are not adequately represented, which skews the priorities of negotiators.

Such culture is deterring new leaders and fresh ideas, weakening its negotiation position and wasting members’ money.

Dr Rachel Ali, representation policy lead for GPC England, said that the exclusion and under-representation of women GPs in the BMA’s organisational structure, both in GPC UK and GPC England, is ‘unacceptable’ and that the BMA continues ‘to work hard to see its reversal’.

‘GPCUK is currently 38% female which, while nowhere near equality, represents an improvement on previous years,’ she told Pulse.

A survey of 713 GPs in England by the Omambala report team found ‘a gender bias towards men’, and that ‘young women are seen to be encouraged but do not get anywhere’.

But there was a wave of optimism in 2021 as the BMA elected the first female chair of GPs in England in its 109-year history.

However, just over three months into her role, Dr Farah Jameel took sick leave, following concerns she had raised about the conduct and sexist culture she experienced within the BMA as GPCE chair.

She was then put on temporary suspension at the end of 2022, following complaints made by the organisation’s staff, and received a vote of no confidence by the GPCE in July last year.

The GPCE has since elected a second woman as its chair, Dr Katie Bramall-Stainer.

Dr Ali said that, with the ‘current vital work’ GPC England is doing in opposing the Government’s inadequate GP contract, the BMA ‘must strive to properly represent the whole profession’.

‘While much work remains to be done we are listening and we are making headway,’ she added.

Since 2019, the BMA’s culture inclusion implementation group (CIIG) has been working on the implementation of the recommendations from the Romney report including the introduction of terms limits and limits on multi-committee membership to improve representation and opportunity across BMA committees, which are due to come in after this year’s annual representative meeting (ARM).

The union also told Pulse that the BMA network of elected women (NEW) has been working since 2020 to ‘champion women and further diversity’ at all elected levels in the association.

‘Wide ranging changes to the structure of the GPC UK have recently been agreed by the committee, and these pave the way for future changes to other GP committees, including ways to improve representation,’ Dr Ali said.

PCNs

Imbalances in representation at leadership level can be noticed in other parts of the profession, including PCNs.

According to NHS England data for PCNs across England, only one in three PCN directors is a woman.

As of February this year, there were 999 PCN GP clinical directors (headcount) and only 330 (33%) of them were women.

Former Streatham PCN director Dr Emma Rowley-Conwy says that leadership roles ‘add to the hours and the pressure’ of general practice, especially for women who still carry most of the childcare responsibilities.

‘Teams or Zoom makes it easier, but colleagues have done meetings on the school run on their mobile – not everyone can cope with this level of stress from juggling demands,’ she said.

‘I am sure this puts a lot of women off. And women still have the bulk of responsibility for childcare.’

She added that while general practice generally has more flexibility than secondary care, leadership roles add to the hours and are paid less than clinical work.

‘A lot of things are unpredictable and not all meetings can be scheduled well in advance, so there is inevitably the need to work weekends and evenings outside core hours.

‘The pay for leadership is substantially less than the pay for clinical work. So financially taking on more responsibility is a really bad decision.’

But she also said that the lack of female representation at leadership level could be linked to the fact that a lot of GPs ‘don’t feel confident’ or ‘are not interested’ in the leadership roles.

‘We are not trained for them, we have to learn how to do the roles on the job,’ Dr Rowley-Conwy added.

‘I think a lot of colleagues just want to focus on the clinical work, which is pressurised enough, and then get out of the practice.’

Former Newham PCN director Dr Farzana Hussain says that she thinks general practice is ‘missing something particularly right up to the top’.

She reflected on an instance when she allowed a salaried GP to work remotely so that she could pick up her child from nursery.

‘I’m not saying a man wouldn’t have thought of it,’ she said. ‘But the only reason I thought of it is because I’ve been in her shoes.

‘Sometimes I think we miss the obvious because it might not affect us and that’s why we need more women to be in a position to be making those decisions, as partners, as clinical directors, as leaders of PCNs. Because they might just understand.’

In response to the figures for female representation at PCN level, NHSE’s primary care director Dr Amanda Doyle said: ‘Over half of GPs are now women, and we are committed to working alongside PCNs and stakeholders to ensure that they have equal access to leadership roles within the NHS.’

It is worth noting that currently, two women GPs are serving in the most senior roles within primary care at NHS England – Dr Doyle, a GP for more than 20 years in a large practice in a deprived area of Blackpool, who became the commissioner’s primary care director in 2022, and Professor Claire Fuller, who produced a landmark review on how to integrate primary care with other NHS services and was appointed medical director of primary care last year.

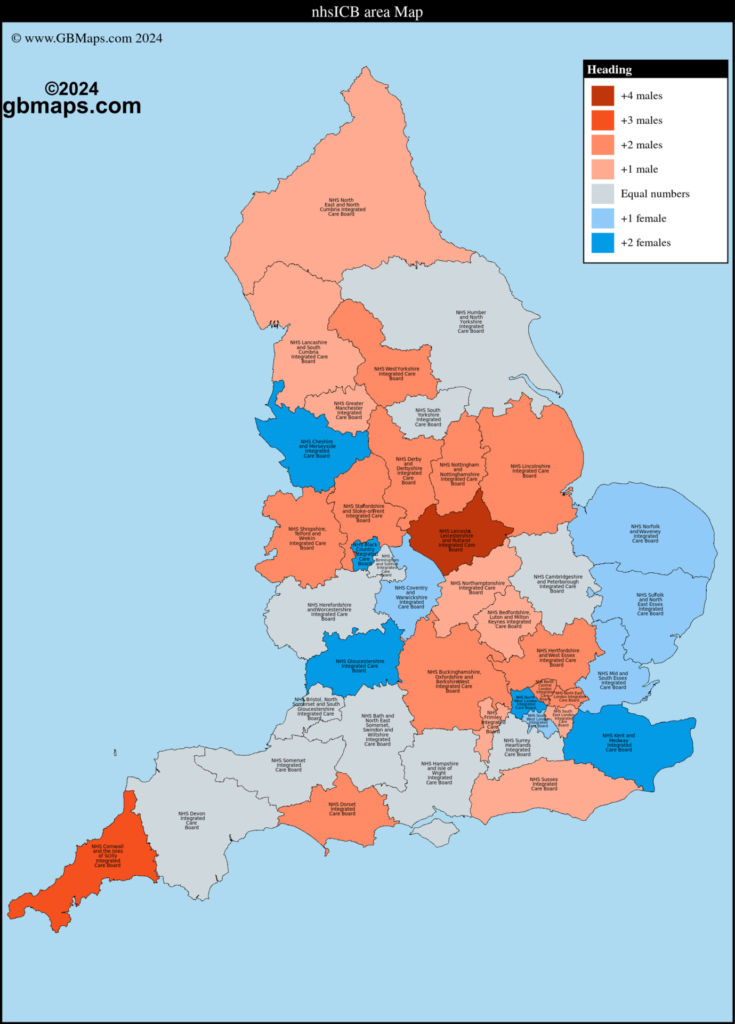

ICBs

According to an analysis by Pulse, which looked at ICB board members as displayed on each ICB’s website, there is currently 110 GPs appointed as ICB board members across England, and only 32 of them are women. Out of 42 ICBs, 15 currently have no women GPs on their board.

It is important to note that this doesn’t reflect the totality of the boards, only the GPs on the boards. But many of the factors that affect female GP representation in other bodies also affect ICB representation.

A GP who asked to remain anonymous and worked with her local ICB says that the ‘attitudes’ of some people in leadership roles ‘make it harder’ for women to get into leadership positions.

‘While it would be good to pave the way for gender equality, there seems to be a chip on the shoulder of some who seem keen to keep other women at bay,’ she said.

‘In medicine I don’t think I have ever really felt disadvantaged by being female, I think my abilities have spoken for themselves.

‘However this is less so in NHS leadership. Men still seem to be the default go-to as authority figures, even if the job titles don’t match.

‘My voice is not heard in the same way as some of my male colleagues’. It’s frustrating as I don’t want to believe that this gender inequity exists, but it’s pretty clear that there isn’t equal respect.’

North East London ICB chief executive Zina Etheridge agrees that ICBs have ‘more to do’ to ensure equal representation.

‘I think there is a general point for public sector leadership, which applies everywhere, which is that can be a bit of a tendency to want a kind of “hero” leadership model,’ she told our sister title Healthcare Leader.

‘And I think, quite often, that’s not the model of women’s leadership. There are lots of men who are not that in that mold, either. But I think women are less likely than men to be in that mold.

‘I think is not the right model of leadership for the complexity of the world that we’ve got. It certainly doesn’t get as many women into leadership positions as you would otherwise get.’

Gloucester ICB chief executive Mary Hutton said that her ICB has developed health inequality fellowships, and different ways of enabling women to have different opportunities earlier on in their career, ‘to test out where they want to develop their talents’.

‘I suspect it isn’t enough,’ she told Healthcare Leader. ‘But I think I think there is an open culture that people can come forward.’

ICBs with no female GP representation

- Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire West

- Cornwall and The Isles of Scilly

- Derby and Derbyshire

- Dorset

- Greater Manchester

- Lancashire and South Cumbria

- Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland

- Lincolnshire

- North East London

- Nottingham and Nottinghamshire

- Shropshire, Telford and Wrekin

- South East London

- Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent

- Sussex

- West Yorkshire

RCGP

The RCGP council seems to buck the trend. It is currently composed of 61 members and more than half are women (35), including the current chair and vice-chair.

College vice chair Dr Margaret Ikpoh says that this ‘isn’t always the case’, and that it is important that RCGP leadership is representative of its members.

‘For quite some time, the majority of GPs in the UK have been women, and it’s really good to see this reflected within the college’s current leadership,’ she said.

‘Four of the last five chairs of council have been women and we’re really pleased to currently have this balance in our leadership team and on our council.

‘This isn’t always the case and in recent history, we’ve had leadership teams that are majority women and majority men – ultimately, these are predominantly elected roles, so it depends who stands and who votes.’

She adds that equality at leadership level allows members ‘to speak collectively with authenticity and experience’ and that members ‘feel heard and that their views are reflected’.

The current composition of the RCGP

- Chair: female

- President: male

- College officers: 2 male and 2 female

- Chairs of devolved councils: 1 male and 2 female

- Nationally elected council members: 8 male and 10 female

- Faculty representatives: 14 male and 20 female

There is still work to do on women GPs in leadership positions. On ICBs, the GPC and PCNs, female GPs are still underrepresented. It was only in 2021 that GPs in England were led by a female GP, Dr Farah Jameel, and she had to leave her role of chair only after facing sexist comments. She was replaced by another female GP in Dr Katie Bramall Stainer, but she remains the only female chair among the four national chairs, and remains a minority on her own committee.

This does have an effect on grassroots GPs. As we have discussed elsewhere, issues around maternity leave and the gender pay gap aren’t at the top of leaders or commissioners’ agendas.

We can’t ignore the progress. But, equally, we need to acknowledge there is more to do.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Related Articles

READERS' COMMENTS [5]

Please note, only GPs are permitted to add comments to articles

Is there are competitive queue of GPs wanting to take on NHS leadership roles?

Half of this article describes quite reasonable reasons why people don’t want to do these roles!

This article assumes equality of outcome is the default target, rather than equality of opportunity? Is that the right approach?

No one wants to do these jobs. In a few years, there will no role of GPs in prisry csre on the watch of RCGP and BMA. This seems a like a waste of energy.

*Primary care

Hunt them down and kill them, we shall not rest till all these vermin have been eradicated

GP “leaders” share a significant part of the blame for the current mess; perhaps worry less about gender and more about competency?