Treatment is aimed at reducing symptoms, risk of microvascular complications such as retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, and risk of macrovascular complications like myocardial infarct, stroke and peripheral arterial disease. This includes the encouragement of lifestyle changes and management of blood pressure, lipid parameters and blood glucose often necessitating polypharmacy. The evidence on the effectiveness of blood pressure and lipid control in reducing diabetes complications is well-established. However, the role of glucose control in preventing cardiovascular outcomes is less clear.

Standard current treatment

Individualised written care plans are recommended for all adults with type 2 diabetes. These should include information on patient preferences, multiple morbidities, current therapies, contraindications to treatments and potential risks from multiple medications. Personalised management plans should emphasise healthy behaviours such as physical activity, dietary changes and promotion of weight loss if appropriate. Evidence on the effectiveness of education programmes has been shown (for example in the DESMOND trial), and therefore referral to a structured education programme is also recommended at the time of diagnosis, with annual reinforcement being encouraged. These programmes should include patient family members or carers. NICE does not make any specific recommendations on exactly which structured education programme is best, but programmes that are aimed at improving patient knowledge, motivation and encouraging self-management could be helpful.2

Diabetes drugs must be considered in the context of reducing overall cardiovascular disease risk, rather than focusing exclusively on tight glycaemic control. Evidence that tight glycaemic control (irrespective of which drug is used) reduces microvascular and macrovascular risk is inconsistent. Since the last NICE guidance on type 2 diabetes, there are several recent and ongoing trials of individual glycaemic agents show conflicting results for cardiovascular outcomes that are yet to be considered by NICE.

The diabetes drug treatment pathway can be divided into those patients who can tolerate (or have no contraindications) to metformin and those who cannot take metformin. These pathways are summarised in figures 1 and 2 below. For those who can take metformin (which will be the majority of patients), standard release preparation remains the first-line agent. Start with a low dose followed by a gradual increase in dose over a few weeks. A slow increase in metformin will limit potential side effects, of which gastrointestinal symptoms are most common. If gastrointestinal side effects are a problem, a modified release metformin might be helpful. Maximum dose of metformin is followed by dual therapy for second-line treatment. NICE recommends metformin with any of the following agents:

- DPP-4 inhibitors – e.g. sitagliptin

- Glitazone – e.g. pioglitazone

- Sulphonylurea – e.g. gliclazide

- SGLT2 inhibitors – e.g. empagliflozin

Further intensification to third-line treatments will include metformin, a sulphonylurea and pioglitazone; or metformin, a sulphonylurea and a gliptin; or metformin, a sulphonyurea, pioglitazone and a gliflozin. Another third-line option is to start insulin treatment, although this must be considered in the context of patient preferences, occupation, frailty and risk of hypoglycaemia.

Fourth-line options could include metformin, a sulphonylurea and a GLP-1 agonist. This is only appropriate in patients with high BMIs (over 35), or where patients are not able to take insulin treatment due the impact on their work, or in situations where weight loss could be helpful in lowering complications of related comorbidities. If, however, a patient is already started on insulin from the third-line treatment then NICE advice is to consider referral to the diabetes team, who could initiate a GLP-1 agonist (such as exenatide) alongside insulin.

It is important to note that while GLP-1 agonists promote weight loss and glycaemic control, NICE recommends continuing this treatment only if sufficient weight loss (3% in six months) and glycaemic control (a reduction of at least 11mmol/mol [1.0%] in HbA1c) is achieved.

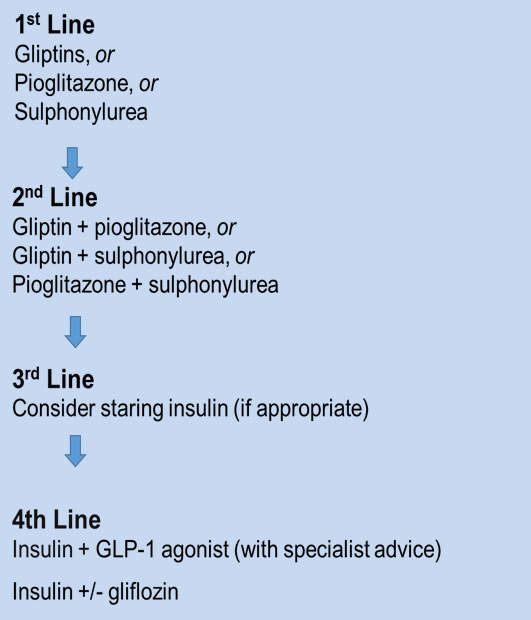

The treatment pathway for managing hyperglycaemia in patients who cannot tolerate metformin or have contraindications, such as renal impairment (eGFR >30ml/minute/1.73m2), is different. This will include a first-line option of a DPP-4 inhibitor, pioglitazone or a sulphonylurea. Second-line treatment should include a DPP-4 inhibitor alongside pioglitazone, or a DPP-4 inhibitor with sulphonylurea, or pioglitazone with sulphonylurea. If these second-line options are ineffective, a discussion with the patient about starting insulin is required. Fourth-line options will include insulin with a GLP-1 agonist with specialist advice or insulin with SGLT2 inhibitor.

Figure 1: Summary of diabetes drugs, if metformin can be taken2

Figure 2: Summary of diabetes drugs, if metformin cannot be taken2

NICE provides several choices of diabetes drugs that can be used in combination at each intensification level. Recent evidence suggests that there are clinically relevant differences between these choices of diabetes drugs with regard to cardiovascular risk and mortality, whether these drugs are given alone or in combination. In 2016, a large primary care study showed that glitazone use is associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease, heart failure and death.3 DPP-4 inhibitors lowered the risk of death and heart failure to a lesser extent and had no effect on cardiovascular disease. Sulphonylureas as monotherapy, or in combination with metformin and insulin, was in fact associated with an increase in heart failure and this has been shown inconsistently with other studies as well. Therefore it would seem that glitazones might be favourable over DPP-4 inhibitors, followed by sulphonylureas, but until NICE updates the guidelines with a thorough review of the newer evidence, this is not clear.

The decision on when to intensify treatment can be difficult and must be considered on a case by case basis. Patient preferences, comorbidities, age and occupation should all be taken into account. NICE does provide target levels for glycaemic control but recommends that clinicians relax tight glycaemic control if, for example, patients are at risk or have previously experienced hypoglycaemia, tight control is not achievable, life expectancy is short enough that prevention of long-term complications is unlikely, frailty is a concern, there are multiple comorbidities or their occupation involves operating heavy machinery. As a guide, the following levels have been suggested from NICE:

- If patients are managed with lifestyle alone or lifestyle plus a single drug that is not likely to cause hypoglycemia, aim for HbA1c of 48mmol/mol (6.5%).

- If patients are taking diabetes drugs that put them at risk of hypoglycemia, the HbA1c should be slightly higher at 53mmol/mol (7.0%).

- Intensification of treatment to two or more diabetes drugs should be considered if HbA1c levels rise up to 58mmol/mol (7.5%) or higher, with a view to achieving an HbA1c level of 53mmol/mol (7.0%).

Intensification of drug treatments in these scenarios should always be alongside reinforcement of lifestyle changes. Be aware of patients who achieve HbA1c levels below the suggested targets. In these cases, discuss symptoms of hypoglycemia and ensure that renal function and rapid weight loss are not responsible, as these can both cause low HbA1c levels.

What’s newly available?

The SGLT2 inhibitors are a new class of diabetes drug that have been recommended by NICE in the last year as monotherapy for hyperglycaemia in patients who cannot tolerate metformin, a sulphonylurea or where a glitazone is not appropriate and a DPP-4 inhibitor would otherwise be prescribed. This has been shown to reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia and is beneficial for weight loss. In addition to the SGLT2 inhibitors, the GLP-1 agonists (such as exenatide, lixisenatide and dulaglutide) are suitable alternatives to consider in combination with other pharmacological agents. These relatively new groups of drugs are particularly useful in patients who operate heavy machinery, such as lorry drivers or factory workers. Injectable formulations are still used but can be administered less frequently than insulin, for example exenatide can be taken once weekly. GLP-1 agonists are also helpful in promoting weight loss. In addition to medication for weight loss, there is recent evidence that weight loss related to bariatric surgery for obesity in patients with type 2 diabetes can also improve glycaemic control.4,5 Recent guidance suggests bariatric surgery could be used for treatment of type 2 diabetes in patients with a high BMI (30-35) and poor glycaemic control. While type 2 diabetes is considered a chronic progressive disease, there is also growing evidence in the literature on remission or cure of type 2 diabetes. This has primarily been reported in relation to bariatric surgery, although there are also cases of partial or complete remission related to intensive lifestyle modification.

What has fallen out of fashion and why

NICE has relaxed its guidance on tight glycaemic control, owing to the risk of hypoglycaemic and clinical variations in patient profiles in practice. There is now greater emphasis on individualised treatment for type 2 diabetes and personalised glycaemic target levels based on patient preferences, associated morbidities, risk of falls and risk of hypoglycaemia.

Self-monitoring of blood glucose is no longer routinely suggested unless the patient is on insulin treatment, at risk of hypoglycaemia or within a particular education programme in which blood testing is used to aid knowledge about diabetes management.

Special/atypical cases and their treatment/tailored treatment

Target levels for patients with type 2 diabetes who are pregnant, breastfeeding or develop gestational diabetes are different, as are drug therapies, and as such NICE has set out a complete guideline specifically for diabetes in pregnancy.

Non-drug options

Lifestyle modification is extremely important in type 2 diabetes. Daily physical activity is recommended for all adults over 18 years (whether or not they have diabetes). The amount of activity required will vary depending on the intensity of the activity. For moderate intensity exercising, an average 150 minutes each week should be encouraged. If the exercise is more vigorous in intensity then 75 minutes of activity would be equivalent. Muscle strengthening exercise twice a week is also recommended. In adults over the age of 65, advice on exercise should be tailored to the patient according to their level of mobility and risk of falls.

Dietary changes can have a significant impact on glycaemic control and reduced risk of complications. Patients should be encouraged to have low glycaemic-index carbohydrates products such as brown bread, brown pasta, lentils, fruit and vegetables. Do not recommend diabetes-specific products and instead encourage patients to have a balanced diet with moderation of sugar and fat. A dietician referral could be helpful with encouraging patients to achieve this, especially in patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight.

Dr Hajira Dambha-Miller is a GP and NIHR doctoral research fellow in Cambridge, with an interest in type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in primary care.

Dr Dambha-Miller would like to thank Professor Simon Griffin for his help reviewing early drafts of the article and assisting with the content.