Pulse in Print: How our investigations shone a light on the profession

Pulse has prided itself on investigative journalism, being the first to highlight systemic problems within general practice. Here, we take a look at some of our powerful recent investigations, and what has happened since they were published

How practice closures became a common occurrence

It’s no surprise that when a GP surgery risks closure, local residents tend to be up in arms – starting petitions, engaging with local politicians, and taking to social media. GP practices are a vital part of any local community. When they close, patients may have to travel miles further for appointments, or may even lose the GP they’ve known all their life.

But a practice closing for good was almost unheard of in the early 2010s. There were examples of practices moving to more modern premises, and of course partners and principals being replaced. But seldom did partners hand their contracts back completely, with patients having to be dispersed to neighbouring practices.

Yet around this time, Pulse heard murmurings that contracts were being handed back. In 2014, LMC leaders told Pulse that more than 100 practices had either closed or faced imminent closure that year, which for many was unprecedented. This caused shock across the profession. It led to Pulse’s ‘Stop Practice Closures’ campaign – a commitment to lobby ministers for emergency support, start an e-petition, and bring GP leaders together to share ideas.

But it seemed the report of 100 practices in danger was a vast underestimation. Five years later, Pulse raised alarm bells again. Freedom of information data revealed that closures had risen almost eight-fold since 2013 and had hit a record high in 2018, affecting half a million patients. By 2021, cumulative figures showed that the total number of closures since 2013 had reached almost 800.

Pulse’s annual investigation in to this was shining a light on this phenomena – this was not being counted by authorities or any other publication.

But there was another story here – how many of those closures were permanent? Last year, for the first time ever, Pulse looked at how many practices had closed for good, and why. Months of poring over data resulted in a landmark investigation, revealing that 474 GP surgeries had closed in the previous nine years without being replaced. Even more importantly, Pulse’s work found that small practices on lower funding in more deprived areas were most likely to be affected. The final straw for most practices was recruitment issues, but many also cited CQC ratings or APMS contracts coming to an end. The figures also revealed that over those nine years roughly 1.5 million patients had been displaced, and as a result some would have to travel miles to access a GP.

These findings did not go unnoticed – they were featured across a spread of national newspapers and broadcasters, cited at the Labour Party Conference, and fed into wider academic work. The investigation also picked up a prestigious award from the Medical Journalists’ Association.

Since a peak of 163 closures in 2018, the number has steadily decreased to the most recent figure of 57 for 2022. But this doesn’t mean the problem is fading away, and the underlying factors of underfunding and dwindling GP workforce are as present as ever.

The number of practices shutting up shop will continue to have a strong domino effect on neighbouring practices. When capacity is already stretched, taking on new patients after a dispersal could push struggling practices over the edge. And smaller practices are more at risk, despite their better scores on patient satisfaction surveys. This is a worrying trend at a time when continuity of care is high on the agenda – both for GPs and the Government.

‘This investigation was a labour of love. It was hard work, sometimes frustrating, often complex, but always worth it. I hope that Lost Practices helped to shine a light on why the worrying acceleration of closures is a trend that needs to be reversed.’ Rachel Carter, Pulse investigations editor, 2021-2023

The recruitment rollercoaster

A March 1967 Pulse front page warned that the ‘GP shortage will intensify’. In the years since, this headline (or derivations) has alternated with those around GPs struggling to find work in a never-ending cycle.

The past decade has seen perhaps the deepest recruitment crisis in the profession’s history, and Pulse has led the reporting on it.

In 2014, we reported that murmurings of an impending GP recruitment crisis ‘had been circulating for a while’. That year, the crisis finally hit. An internal BMA GP Committee briefing paper described the possible effects as ‘catastrophic’, with general practice suffering permanent damage. A Pulse investigation confirmed these fears, showing that one in 10 partnership vacancies were going unfilled for more a year, and a quarter were vacant for more than six months.

The toxic cocktail of problems listed by the GPC at the time sounds familiar – rock-bottom morale, rising workload and underfunding were cited as major reasons for many GPs rejecting partnerships and choosing instead a better work-life balance as a sessional GP. And the denigration of general practice by Government and in the media was also a huge component in driving GPs out of the profession 10 years ago.

In subsequent years, GP recruitment has been used as a political football, especially in England, with various health secretaries making promises to increase the GP workforce by 5,000 (Jeremy Hunt, 2015) and 6,000 (Sajid Javid, 2019). Since then, the number of fully trained full-time equivalent GPs has decreased.

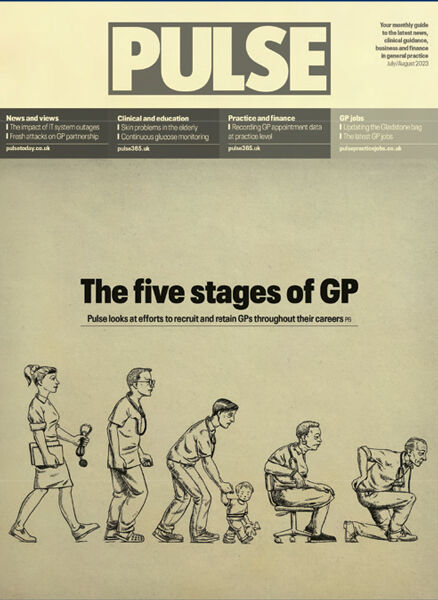

Pulse’s most recent investigation in July 2023 reviewed data spanning the stages of a GP’s career to determine why and at what stages the NHS was losing GPs. While the number of new fully-trained GPs was relatively healthy, there were worrying trends among GPs at the height of their careers, who reduced their hours due to serious stress and burnout or considered working abroad for better work-life balance or leaving the NHS to work privately. Retaining older GPs continued to prove tough for health authorities, with more GPs are taking early retirement, or cutting their hours as they reach their 60s.

NHS England’s workforce plan promised to ‘train more NHS staff domestically’, increasing GP training places in England by 50% to 6,000 by 2031, and trainees’ exposure to general practice at both foundation programme level and GP specialty training will also be increased. But a Pulse analysis of the measures showed they would require a doubling of training capacity in general practice within five years, and a trebling within ten. Yet there seemed to be nothing in the plan to outline how this will happen.

Practices are continuing to struggle to recruit GPs. However, in the latter stages of 2023, it looked as though there might be a shift. Locums were reporting that work ‘literally disappeared overnight’. A Pulse survey of 612 GP partners found a 44% reduction in the number of GP vacancies advertised since the previous year, a 23% reduction in the number of vacancies since May that year and around half of GP locums reporting a decrease in their sessions worked over the past year due to a lack of work available. This was due to a number of factors, according to GP leaders, including an increase in the ARRS success in hiring staff and a lack of resources and space to house GPs. The rollercoaster gives no sign of stopping yet.

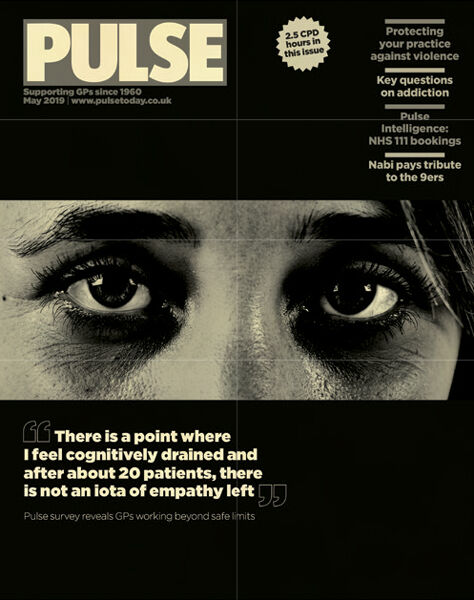

GP burnout becomes a hazard of the profession

GP burnout is now sadly a permanent feature of the profession. Yet pre-2010s, it wasn’t something that was discussed too much. That may be due to a change in societal attitudes towards mental health, or because of increasing workloads – or most likely both.

Pulse had a seminal part to play in raising the issue. In 2013, it launched its Battling Burnout campaign bidding for GPs to receive support as rising workloads were increasingly impacting their mental health. At the time, Pulse used a validated questionnaire, the Maslach Burnout Inventory tool, adapted for GPs, to show that some 46% of the UK’s were at high risk of burning out. Worryingly, 43% of GPs reported high levels of depersonalisation and a stark 97% didn’t think they were positively influencing other people’s lives or achieving something worthwhile as part of their job.

This campaign had clear success: in 2016, NHS England announced it was investing £16m in mental health support for struggling GPs, as part of a new national service, citing the Pulse campaign

Led by Professor Dame Clare Gerada as its medical director, the NHS Practitioner Health programme was made available free of charge and open to self-referral for all types of GPs across England. It is also open to regulated health and care staff in Scotland.

Professor Gerada, who has since stepped down from that role but who remains a staunch campaigner for GP mental health, says: ‘I think it has had a phenomenal impact. It has saved lives, that’s for sure. I fundamentally think it has saved lives, lots and lots of lives.

‘It has saved jobs, it has saved careers and it has saved patients, because it has helped a lot of medical doctors to carry on working.’

However, although GPs have now got dedicated support, the underlying issues creating burnout do not seem to have improved.

In 2019, Pulse’s first-ever GP workload survey showed how dangerous levels were jeopardising patient safety. An average working day comprised 11 hours, including eight hours of clinical care, the findings showed. And GPs working full time had an average 41 patient contacts a day – far higher than the 30 contacts that respondents called a safe limit at the time. By 2021, when Pulse repeated the survey following Covid, the results were broadly similar.

The 2023 Health Foundation report, Stressed and Overworked, which analyses international survey data from the Commonwealth Fund, found ‘satisfaction has fallen over time across most countries’ but the UK scored worst on key areas including overall job satisfaction, work-life balance, workload, time spent with patients.

However, the UK’s GPs are taking things into their own hands and are changing their working patterns to protect their mental health, with a greater number deciding to work less than full time and take salaried positions. At the same time, the BMA has recommended that GPs cap consultations at 25 per day. It is understood they will push for this in the next major contract negotiations.

For the moment, however, burnout remains a common feature in general practice. Former BMA chair Dr Chaand Nagpaul, a trustee of Doctors in Distress, says: ‘We’ve had GPs – partners – whom we have lost due to stress and burnout.

‘Burnout is very real. A BMA survey shows that eight in 10 GPs reporting symptoms of stress, anxiety, or depression. These are very serious statistics. And also one in four GPS say that they know of someone who had taken they know of a GP who had taken their own lives.’

GPs and Pulse will be continuing to battle burnout for a good while longer.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.