In a major Pulse analysis, Anna Colivicchi asks whether the Government’s long-term workforce plan for GPs will solve any of the longstanding problems

‘This is a truly historic day for the NHS in England,’ said NHS England chief executive Amanda Pritchard on the publication of the long-awaited workforce plan at the end of June. The plan commits to an extra £2.4bn to address what it warns could be a shortfall of 360,000 staff by 2037.

And this shortfall affects general practice more than any other part of the NHS. It is an oft-repeated fact that in England we have lost more than 2,000 fully qualified full-time-equivalent GPs since 2015.

The workforce plan estimates a shortfall of 15,000 FTEs by 2036. To counter this, it includes more medical school places and training positions. But will these work?

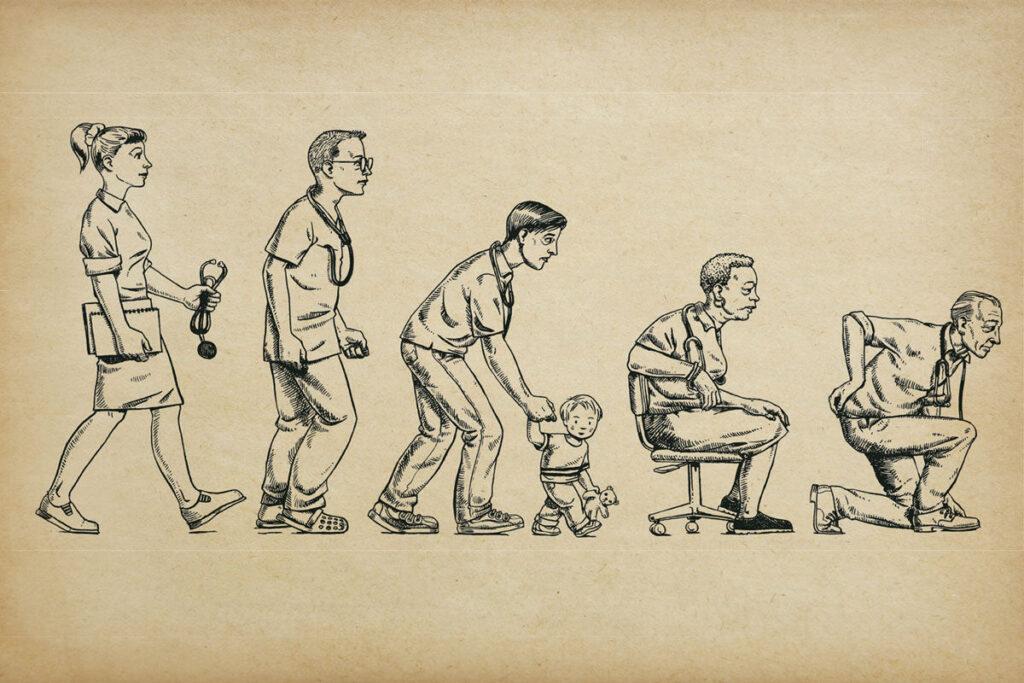

A major Pulse analysis reviews data spanning the stages of a GP’s career to determine why and at what stages we are losing GPs, and asks whether the Government’s latest plans will help solve the biggest crisis currently facing general practice.

Stages 1 and 2: Boosting GP training numbers

There is political consensus around the need to boost medical school places to support GP workforce numbers. But little has been done to map how such an increase will translate to fully trained full-time-equivalent GPs.

So Pulse looked at medical school starters in 2012 – who, with a linear career progression, became full-time GPs in August 2022. While there are caveats around non-linear progression – gap years, career breaks and exam failures are all factors – our analysis reveals roughly a third of this cohort went on to become fully trained GPs.

Medical schools

Currently, there are around 9,500 places to study medicine in the UK each year.1 The workforce report has pledged to double the numbers in England from 7,500 to 15,000, which is in line with calls from Labour and the Medical Schools Council.2,3

The RCGP has in the past pointed to a ‘toxic anti-GP culture’ in some academic institutions, which the Government has tried to counter by increasing funding for medicals schools that aim to boost GP trainee uptake by exposing students to general practice. The Department of Health and Social Care has said it believes ‘giving students additional exposure to high-quality placements in general practice will improve recruitment into these specialties’.

Five medical schools were set up in 20184 – Sunderland, Edge Hill, Anglia Ruskin, Lincoln and Canterbury – as well as an expansion of places at Aston, and they all had to show a GP focus to get GMC approval.

The workforce plan says the Government will look at setting up more medical schools in areas of the country where there is the greatest staffing shortfall, with similar plans for postgraduate medical training places.

Foundation training

During the foundation programme, around 50% to 55% do a four-month rotation in general practice. Those who do spend time in general practice are seen as being more likely to choose to be a GP.

Under the plan, all foundation programme trainees will do a rotation in general practice by 2030/31, which ‘will give doctors in foundation training an understanding of work in primary care’. In the near term, HEE will place as many applicants as possible in their preferred foundation programme, instead of ranking them by grade within their medical school, which many saw as unfair. This change is unlikely to have much effect on GP training, however.

GP speciality training

Given the recruitment issues across the NHS, attracting trainees to GP specialty training is a relative success for HEE. Numbers are up from 2,671 in 2014 to over 4,000 in 20235 – half of all foundation programme doctors.

This has been achieved through a series of initiatives, including the ‘Choose GP’ PR campaign6 and £20,000 salary supplements to attract trainee GPs to areas where training places have been historically difficult to fill.7

As part of the workforce plan, the Government is promising to increase GP training places by 50% to 6,000 by 2031. GP registrars have traditionally spent around half of their three-year specialty training in general practice, but as part of changes included in the plan, they will now spend their full training in general practice.

But there is little in the plan regarding who will train this new intake. There have been problems with finding trainers, and part of this is due to problems with premises. The plan acknowledges this, but its solution seems underwhelming: ‘We will work with stakeholders, informed by the issues we identified through a discovery exercise in 2022/23, to ensure clinical placements are designed into health and care services, and placement providers know what core standards they need to meet’.

How training affects future GP workforce

While the conversion rate from medical students to fully trained GPs is healthy, potential problems lie in wait.

RCGP chair Professor Kamila Hawthorne says GP trainees may be put off when they witness the workload faced by their trainers and other GPs in the practice.

A BMA survey found 13% of GP trainees say they don’t expect to work as GPs in future8, which, if extrapolated, represents a loss of 433 potential GPs in England alone.

Stage 3: Mid-career GPs cutting hours and leaving

Perhaps the most worrying trends are among fully trained GPs at the height of their careers. The data relating to GPs aged 30-50 who are leaving the profession are limited but concerning.

The biggest factor in the decrease in full-time-equivalent GPs may be the number taking less-than-full-time (LTFT) roles. While in the past eight years the headcount of fully qualified GPs has slightly grown, this has not translated into an increase in the FTE workforce. This is because the average GP now works less than in 2015 – and the 30-50 age group has seen the biggest change in this respect (see chart above). This trend looks set to stay: a survey of Pulse readers in June found that of those still working full time, 45% in this age bracket are looking to reduce their hours.

The RCGP says ‘large numbers of female GPs in the 30-34, 35-39 and 40-44 age cohorts are leaving the workforce’ and ‘may be leaving due to childcare or general caring responsibilities’.9

However, due to the intensity of the workload, ‘less than full time’ might be misleading. Pulse’s survey reveals that LTFT GPs work on average 4.6 sessions and more than 25 hours a week. But the RCGP has pointed out that unlike secondary care clinicians, GPs typically do not have protected time in their contracts for admin, professional development or teaching. Also, many GPs who work less than full time in the surgery often have essential roles outside of routine work, such as PCN work, commissioning roles, extended access, research and teaching.

But the main reasons for GPs wishing to work less continue to be stress and burnout. And this doesn’t just lead to reduced hours. The Pulse survey reveals that almost one in five of the 30-50 age bracket is considering working abroad. According to the GMC, GPs are twice as likely as specialists to cite burnout as a reason to move and only 9% who do emigrate are likely to return, compared with 25% of specialists.10

Australia and New Zealand are the most popular destinations, and the Australian Government put electronic billboards at picket lines during the junior doctor strikes, advertising beautiful landscapes and the work and lifestyle perks on offer to doctors.

Other GPs are considering private work. When digital-first GP provider Babylon controversially entered the market, a striking element of its growth was the ability to recruit early-career GPs, with Ipsos MORI finding in 2019 that their recruitment practices provided ‘learnings for policymakers and the profession as a whole’.

Worryingly, the workforce plan offers few concrete measures to support the retention of these doctors.

Stages 4 and 5: Older GPs considering early retirement

Retaining older GPs has proved tough for health authorities. More GPs are taking early retirement, or cutting their hours as they reach their 60s.

Figures obtained by Pulse through an FOI request to the NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA) – which is responsible for the administration of pensions – showed that retirement and early retirement figures are returning to pre-Covid levels.

Pulse’s survey found almost half of GPs over 50 are considering leaving general practice altogether. Manchester GP Dr Steve Taylor, a spokesperson for Doctors’ Association UK, says some GPs may have ‘delayed’ retirement due to the pandemic, but continued uncertainty will see them moving on now.

This is a real problem – around four in 10 fully qualified, FTE GPs were aged 50 or over as of April this year.

A key consideration for older GPs has been pensions taxation, which for some meant that working was actually costing them money. In March’s Spring Budget, Chancellor Jeremy Hunt announced reforms to taxation and, as a result, he estimated 80% of NHS doctors each year will not receive a tax charge with respect to accruals under the 2015 NHS career average scheme. This change was welcomed, with the BMA saying it could be ‘potentially transformative’ for the NHS. However, it warned Mr Hunt’s move would have come too late for many, who have already made plans to retire.

There was little in the workforce report to counter this. NHS England had published guidance to help retain doctors in the later stages of their career, including fewer on-call/out-of-hours responsibilities, job sharing, annualised hours contract and remote working.

But despite these efforts, for many GPs approaching retirement it may be financially preferable to leave rather than work reduced hours. Chair of the Association of Independent Specialist Medical Accountants (AISMA) Deborah Wood says the reasons for this include the ‘lack of inflation-proofed funding being made available across the GP contracts, falling profits available for GP practitioners, and the level of tax and pension contributions having to be funded out of those profits’.

However, the main factor impacting GPs coming to the end of their career is the same as for their younger colleagues: burnout. A GMC survey of 13,000 doctors revealed that burnout and stress were the most common factors pushing GPs to leave the profession early.11 A change in taxation rules, it seems, is not enough to make the profession tolerable for many.

The contingency plans

The reaction to the workforce plan from the profession was muted. Although it offers positives in the form of GP training places and the expansion of medical schools, there is little focus on retention.

The plan has a number of measures that seem to admit defeat on this. The most prominent for general practice involves introducing staff and associate specialist (SAS)doctors into primary care – doctors who are below CCT level but are not in training. It says the number of SAS and locally employed doctors – a similar grade – has increased at six times the rate of GPs. A high proportion of these doctors have trained overseas.

The use of SAS doctors was first proposed by the GMC, and NHS England is setting up pilots. GMC chief executive Charlie Massey has emphasised that, rather than replacing GPs, these roles will support them as part of multidisciplinary teams. However, GPs have pointed to issues around supervision and training, and the additional workload this will entail.

There is also a further emphasis on non-GP roles. NHS England says it is going ‘to extend the success’ of the additional roles reimbursement scheme (ARRS) by bringing in 15,000 non-GP direct patient care (DPC) staff and more than 5,000 primary care nurses. But although the ARRS appears to have delivered impressive results – it has met the target of 26,000 new additional staff in general practice – GPs have highlighted problems around the availability of the right staff, as well as the time needed to provide supervision.

The plan’s newest recommendations surround the use of technology, especially AI, which was health secretary Steve Barclay’s focus ahead of publication. The plan claims AI can help with diagnostics, administrative support, predictive health analytics, patient triage and preventive healthcare. Within primary care specifically, it highlights automated dispensing, remote monitoring, including blood pressure, and the use of pulse oximeters.

It may be a case of better late than never, but in terms of alleviating the current pressures in general practice, unfortunately this plan does not do much. Even if it could prove effective in the longer term, will enough GPs be around to hold the fort until increased education and training start to bear fruit? We can only hope.

References

- Lewis J. The cap on medical and dental student numbers in the UK. House of commons Library, March 2023. Link

- Wilkinson E. Labour pledges to double the number of medical school places. Pulse, September 2022. Link

- Medical Schools Council. The expansion of medical student numbers in the United Kingdom. October 2021. Link

- HEE. New medical schools to open to train doctors of the future. March 2018. Link

- HEE. Over 4,000 trainee GPs accepted on placements. November, 2022. Link

- HEE. Choose GP. Link

- NHS England. Targeted Enhanced Recruitment Scheme. Link

- Strachan-Orr E. GP training needs reform: the status quo isn’t working for anyone. BMA, May 2022. Link

- RCGP. Fit for the future. September, 2022. Link

- GMC. Completing the Picture report. October, 2021. Link

- GMC survey reveals reasons doctors quit UK working and what stops them returning. October, 2021. Link

- Eng B. Medical school places: distribution and availability of places in the UK. Medical Teacher 34;2012:5. Link

- HEE. Recruitment Stats and Facts. Interim report, 2017. Link

- DHSC. Written evidence to the Review Body for Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration (DDRB) for the 2022 to 2023 pay round. Link

- Colovicci A. One in three medical school students end up in general practice. Pulse July 2023. Link

Pulse survey

The survey was open between 9-19 June 2023, collating responses using the SurveyMonkey tool. A total of 860 GPs working across the UK responded to the survey, including 425 full-time GPs and 399 less-than-full-time GPs. The age breakdown was: 394 31-50-year-old; 361 51-65-year-old; 57 over 65. The survey was advertised to our readers via our website and email newsletter, with a prize draw for an £250 John Lewis voucher as an incentive to complete the survey. The survey is unweighted, and we do not claim this to be scientific – only a snapshot of the GP population.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

‘Less-Than-Full-Time’ is a dangerously inaccurate term to use for a GP who may be LTFT, but working more than 45 hours per week if a Partner – on top of which they have to set aside from their ‘personal time’ sufficient for CME and appraisals, etc.

A salaried GP can do FT at 35 hours per week (inclusive of 4 hours of CME, so actually only 31 hours); whereas the equivalent number of hours put in by a GP Partner would be defined as only 3 days, which is, I believe, called ‘Half Time’ and equated to a 13 to 19 Hour per week hospital doctor position, in terms of pension, etc.

Bear in mind that the standard ‘full-time’ week for anybody else is only 35-37 hours, unless you are an MP on 2-hour weeks or a PM on all-week parties.

Full time week for a GP Partner, could easily be over 65 hours per week, plus some admin they forgot to count how long they spent doing it.

Was it always like this?

Background, methodology including study design, results and conclusions. I missed all the stages. There was a survey given to some people at sometime in some place. These people were selected on the basis of I don’t know what. We heard some rumours from x but didn’t ask them for their data to check what they said, not our job. We then went to Y and did an FOI and retirement levels are back to pre Covid levels. Yes that’s no surprise and? Are we still doomed?

I’m too grumpy and critical I should retire soon.

£2.4 billion / 360,000 staff is about £6700 each.

GP seniority payments were a retention carrot long since removed which was a dumb move !

If you want the experience and retention of the most committed older GPs you have to make it worth their while and whilst seniority payment was not a fortune it probably helped to retain GPs for a little longer

Not much point training more GP’s when there arn’t the jobs for them to do. More GP’s means more salaries to pay and there isnt the money in primary care. The only way forward is overprobduce GP’s so the few with a post can have all the workload dumped on them or they just get replaced. It;s the chepest way especially when they have to pay for their own training. Who cares.