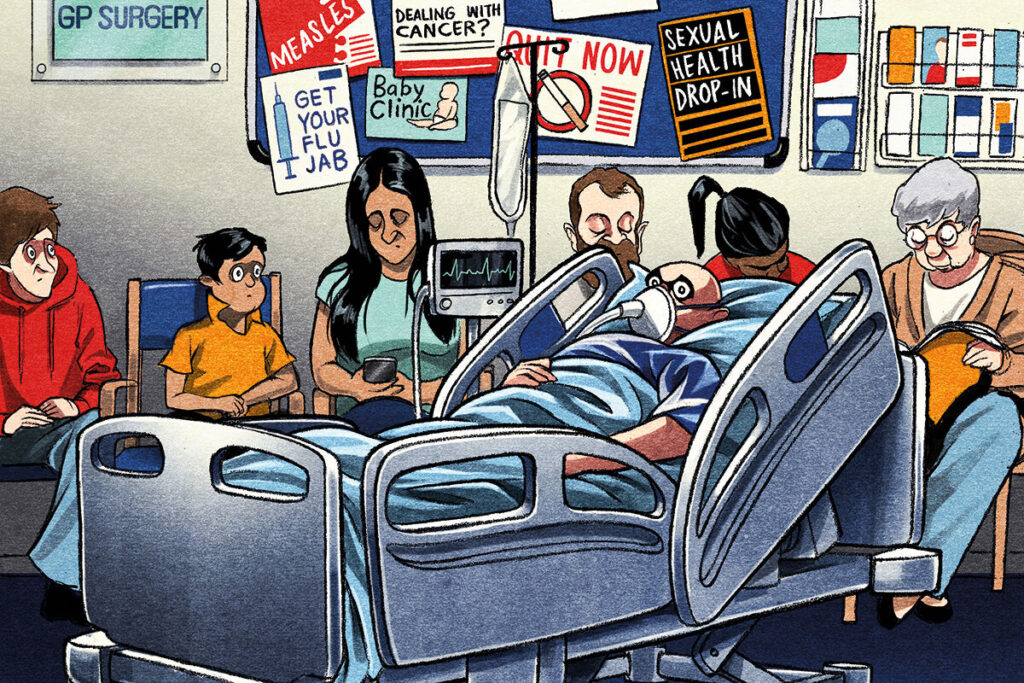

As the hellish winter for emergency services continues, Rachel Carter looks at the impact on general practice

It’s the start of the New Year and a surgery in Wales gets a call from a family. Their relative had gone into respiratory arrest and had needed to be resuscitated. After successfully performing CPR, they were initially told an ambulance would take eight hours and to call the GP instead. In the end the ambulance service dispatched a crew much sooner, but this initial response was ‘astonishing’, a GP at the surgery tells Pulse.

‘There was nothing we could meaningfully offer this patient, they needed to be rushed into hospital immediately. I sent out one of the team, but really there was nothing we could do other than support the family while they waited.’

This experience is becoming all-too common. Ambulance staff strikes across the UK have exacerbated pressures but GPs do not blame the worers. Instead, the disputes are seen as a symptom of how emergency services – and the wider NHS – have been allowed to deteriorate.

Over the festive period more than a dozen ambulance services and NHS trusts declared critical incidents. In December, Category 2 ambulance calls – which include strokes or heart attacks – took on average more than an hour and a half against a target of 18 minutes. The president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine has warned 500 people could be dying each week due to emergency care delays.

The knock-on effect on general practice is severe. A Pulse investigation has revealed harrowing accounts from GPs as they face decisions over whether to transport patients to hospital themselves, and deliver urgent care in their consultation rooms. There is also a lack of clarity over where they stand if things go wrong.

Year-on-year rise in response times

Ambulance response times are steadily worsening – and the most recent data do not even include the current winter. A Pulse survey reveals the extent of the problems for GPs. A GP working in London recalls the recent case of a patient with very complex cardiac history who came to the surgery with chest pain and needed to go to hospital. It was a ‘clear-cut’ Category 2 call. The ambulance took 80 minutes to arrive – it should have taken 18.

A GP in Surrey called an ambulance for a patient in type one respiratory failure in November. They were told there would be a three- to four-hour wait. The practice would have run out of oxygen so had no choice but to bundle the patient, with oxygen, into a staff member’s car and drive them to hospital.

Since the survey was conducted in November, there has been a winter from hell. Category 2 calls in England – which also include severe burns and chest pain – took an average of 92 minutes in December. The GP working in London says: ‘Our whole view on when to call an ambulance is markedly different from two years ago, because we know the service just doesn’t have the capacity to cope with anyone who isn’t in the most immediately life-threatening scenario. We know we have to manage that risk one way or another.’

The GP recalls a parent whose baby was having difficulty breathing and was hypoxic. The GP called an ambulance as they did not feel it was safe for the patient to be taken to hospital via any other method of transport. ‘The wait time to call them back was so long that they weren’t answering the phone. We ended up having to put the child and parent in a taxi to hospital, which felt really unsafe. ‘It leads to that feeling of I need to make sure this child’s got to hospital okay… you have no way of knowing if something happens en route.’

Another GP working in England says uncertainty over exactly when an ambulance will turn up is a key problem. Their practice is within walking distance of a hospital and in some instances, they have resorted to pushing patients to A&E in a wheelchair. The GP recalls a patient who ‘staggered into the surgery’ with sepsis and was ‘horribly unwell’.

‘The ambulance service couldn’t give us a time… In the end the ambulance took probably three-quarters of an hour, but by that time my colleagues had actually taken the patient to hospital.’ Although average response times for Category 4 cases are meeting targets, when there are delays, they can be severe. A GP in Shropshire tells Pulse of a home visit to a patient with dementia who was unable to get out of bed and wasn’t eating or drinking. The GP booked an admission. The response should have been within four hours; the ambulance took 40 hours to arrive.

Are GP practices seen as a ‘safe place’ by 999?

A major concern among GPs is that surgeries are being perceived as a ‘place of safety’ by ambulance services and so a response to a call from a GP takes longer, even though practices are not equipped to manage patients needing emergency or urgent care.

Official data from NHS England, covering callouts from healthcare professionals – and not necessarily GPs – point to a 90-second difference for the most serious (Category 1) if the call is from an HCP. For Category 4, responses to the public are much quicker – although this may be because targets to attend HCP calls are less strict than those to attend calls from the public. The Association of Ambulance Chief Executives told Pulse the process followed by ambulance services across the UK is ‘specifically designed to ensure that HCPs get parity of response for the higher acuity calls’. However, GPs tell Pulse they feel calls are being downgraded when emergency services realise the patient is at a GP practice.

One GP responding to Pulse’s survey commented: ‘We have been told by paramedics that as we are

a place of safety, the response time is always going to be longer – [this is] hotly denied by the trust.’ Another said: ‘We are classified as a safe space so go down the pecking order. This has meant waiting after closing time for ambulances to arrive.’ A GP in Wales – where there is a green, amber and red system – says they believe there may be an ‘unofficial policy’ of downgrading calls coming from surgeries: ‘We would only ring for an emergency if we were worried. We have the patient in front of us, we’ve assessed them and we feel we need the highest priority.’

They add: ‘I think we are all mindful of the pressure that the whole system is under, but I think there is a groundswell of opinion that, wrongly, surgeries are felt to be a safe place.’ They recall a case where a patient in their 60s was brought into the surgery by their partner. Their breathing was failing and their oxygen levels ‘way too low’. The GP says the ambulance service did not give the call priority and said a response would be ‘some hours’. The GP receptionist had to travel to two neighbouring surgeries to ask for their supplies of oxygen.

For GPs, there are a number of problems with such scenarios. First, there are the medicolegal implications – if things go wrong, who is to blame? Second, attending to these situations takes time – hours in most cases. This has a knock-on impact on the already creaking primary care system and GP workload. GPs spoke of having to cancel entire lists or of trying to monitor a patient waiting for an ambulance in one consultation room while at the same time running a busy clinic. And third, surgeries simply do not have all the necessary equipment to provide the care required.

Clinical responsibility

The pressures on the ambulance service are also resulting in paramedics requesting more support from GPs, whether that’s prescriptions, calling for advice or passing over clinical responsibility when a decision has been made not to convey the patient to hospital. One GP tells Pulse: ‘We’re having a lot more calls that the ambulance service is not going to respond within eight hours or even days sometimes, and the family has been told to ring the GP and ask for them to come out and assess.’

Another GP recalls a conversation with a paramedic that left them feeling unhappy: ‘A patient had potentially had a long lie [where a patient is floorbound for a significant period], which because of the risks to the kidneys, you would normally admit them. The paramedic said “I’ve spoken to my supervisor, and they said the patient is fine to stay at home and could somebody from your surgery pop out to have a look at them?”.’ The GP said no, but told Pulse: ‘That’s never happened before.’

FOI responses to Pulse from ambulance trusts show an uptick in referrals to GPs from urgent care services in 2020/21, when Covid hit, which has been more or less sustained since. The 2022/23 figures have been extrapolated without including winter pressures, suggesting they will be worse this year.

A quarter of GPs responding to Pulse’s survey said they ‘often’ felt pressure to provide care in the community for patients they felt ought to be conveyed to hospital. One GP said: ‘I think they are trying hard not to take patients into overloaded EDs, but we are managing increasingly unstable patients who would previously have been admitted.’

GPs given ambiguous advice over their clinical responsibility

There is no definitive advice for what course of action GPs should take when left with an emergency patient. The BMA has said that while GPs always want to help patients, they should not be put in a position of having to do things ‘above and beyond their skills, outside of their contracted services, or not covered by indemnity’.

The Medical Defence Union meanwhile acknowledges that GPs are being forced to consider whether to provide additional treatment in a practice setting. It advises that in these instances, they should keep careful records of the circumstances but adds that deciding what treatment is appropriate is a matter for the ‘doctor’s judgement’. The MDU also advises that where GPs do choose to transport patients to hospital, they should be mindful of insurance stipulations.

The GMC says it has no role in providing legal advice or in setting clinical care guidance, but it expects doctors to follow the principles in its guidance and ‘make the care of their patient their first concern, working within their competence and using their professional judgement to assess risk and deliver the best possible care for people in the circumstances’.

It also highlights the importance of keeping patients’ medical records up to date.

Where do we go from here?

The extreme pressures on the ambulance service have led to strike action in recent months, with workers in England, Wales and Northern Ireland campaigning over pay and staffing (staff in Scotland called off similar action after a deal was reached). The walkouts prompted one PCN in Warrington to hire a private ambulance for a day in January in case any patients from their six practices needed urgent transfer. Before Christmas, NHS England asked GPs in London to consider providing clinical cover for ambulance staff during strike action. And a letter sent to GPs from the North West Ambulance service said ‘immediate self-conveyance or taxi conveyance’ was advised on strike days in all circumstances except ‘confirmed cardiac arrest and immediate threats to life’.

Despite their sympathy for emergency care colleagues, the deteriorating service is leading GPs to consider their own role. Respondents to the Pulse survey questioned whether GPs working in those settings should be trained in advanced life support given the delays. Others are asking whether their surgeries should stock more drugs, oxygen or fluids for when they’re monitoring seriously unwell patients while they wait for an ambulance.

As the crisis deepens, staff are trying to adapt. As one concludes: ‘We are trying to ensure staff are well trained and really on it when it comes to the use of emergency equipment, and are able to do everything needed to stabilise our patients. But it is an added pressure, something that is worsening. And the concern is it will continue to worsen unless something is done about supporting the ambulance service and actually addressing their issues.’

But it is taking a heavy toll. Patients are suffering and GPs are incurring moral injury. The GP adds: ‘You just feel like you’re not able to do the best you can for your patient. I think that’s probably it in

a nutshell… it’s worrying, it’s anxiety provoking, but more importantly, it’s just not good enough.’

READERS' COMMENTS [3]

Please note, only GPs are permitted to add comments to articles

We don’t have any staff with personal cars insured to carry oxygen cylinders (and no staff personally licensed to carry compressed gas cylinders and buy and sell them) from the next practices, over 30 minutes away from us at the closest, and next 45 minutes.

But practices Directly managed by the Health Board, can have porters bring gas bottles from the main hospital 2-3 hours away if they want to.

Where did the 18 minute ambulance response target time come from?

It is supposed to be within an EIGHT-minute average!

So when the labour party get into power at the next general election and they dismantle general practice as planned, replacing it with an endless list of job advertisements for “salaried practitioners”, who will the ambulance call handlers tell people to contact when they don’t have an ambulance crew to send..the NUS careers website maybe?

Oooh look!

Loads of colourful pie charts taken weeks to compile, lots of money to fund

All stating the bleedin’ obvious!

Was this commissioned by Dame Whatsername with the RCGP colouring books?